Missed part 2 of our “Neuro-mental health” series “Stress, strain and fracture”? Read on here.

Why do we focus so intensively on stress and trauma at epiAge? Because poor neuro-mental health causes ageing to the core of our cells. In fact, trauma not only affects individual health but may, in extreme cases, epigenetically burden further generations.

You hate military action films, and you can’t stand Sylvester Stallone?

Great! Then, we still challenge you to watch the scene where John Rambo breaks down in front of Colonel Trautman, without shedding a tear, or at least vicariously experiencing some of the distress exuded by both men. “First Blood” (1982) is iconic for its gripping description of PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder] and is considered one of the flagship films of what has subsequently been described as the “vetsploitation”(the portmanteau term for “veteran exploitation”) subgenre.

In fact, trauma and its acute chronic presentation as PTSD are intimately linked to the world of war. Indeed, there is hardly any other context providing for such a concentration of unpredictability, shock, violence and suffering – both human and material.

And it is the struggles of Vietnam War veterans to readjust to civilian life that at last provided the impetus to include PTSD in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-lll) published by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980. However, it took years of intense lobbying by veteran associations, affected families as well as medical professionals for PTSD to be taken seriously.

Indeed, First Blood was not the first film to depict trauma in veterans. “Let There Be Light”, John Huston’s documentary portraying the challenges of soldiers after World War II, was produced in 1946, long after the first modern accounts of “shell shock” had leached out of the bloody trenches of World War I.

However, its stark representation of what was then informally also called “neurasthenia” or “war neurosis” meant that the U.S. Army took great pains to censor it. In fact, it wasn’t until 1980 that it was publicly screened. Understandably, the emotional distress evoked in this documentary and subsequent vetsploitation films was considered bad PR for the recruitment of new soldiers.

So, for most of the 20th century, suffering from “shell shock” was considered a physical and moral weakness. And although specialised treatment modalities began to slowly emerge beyond classical “talk-centric” psychotherapy or psychoanalysis, symptoms were often brushed under the carpet.

Does this mean that trauma and the concept of PTSD only emerged in the latter half of the 20th century?

No. The word trauma stems from Ancient Greek and means “wound”. Originally it referred to physical rather than emotional wounding. It is only in the course of the 20th century that trauma’s meaning began to shift towards the latter. However, powerful echoes of the physical and psychological terror stoked by battle and other adversities can be found in countless legends and writings throughout history.

Hence, it is probably the sheer volume, the intensity and the long-term consequences of trauma – as powered by industrialised warfare on an increasingly global scale – that provided the momentum and pressure that veterans needed to have their suffering recognised.

Characteristic of the type of traumatic event recognised by the DSM-III was that “[…] it was perceived as a catastrophic stressor that was outside the range of usual human experience. The framers of the original PTSD diagnosis had in mind events such as war, torture, rape, the Nazi Holocaust, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, natural disasters (such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and volcano eruptions), and human-made disasters (such as factory explosions, airplane crashes, and automobile accidents).” (Friedman, s.d.)

Painful events anchored in run-of-the-mill civilian life such as the death of a child, domestic violence, acute illness, redundancy or bankruptcy were not considered “traumatic”. And any difficulty coping with them was labelled an “adjustment disorder” since most individuals were deemed capable of managing these challenges.

So, how did “everyday trauma” gain the visibility that it has today and when was it at last taken seriously?

This other “branch” of trauma evolved much more discreetly throughout history. Various physical ailments and neuroses, primarily affecting women and described under the blanket term of “hysteria”, were obsessively studied and treated by physicians and members of the clergy from Antiquity to the 19th century. These maladies tended to be ascribed to issues with the female physiology, most centrally the womb (hystera in Ancient Greek) and “therapies” involved anything from plant medicine, vibrators and marital intercourse to exorcism and burning at the stake.

When neurologists, psychiatrists and psychologists took over the treatment of hysteria from general practitioners in the late 19thcentury, another dimension began to emerge.

It was pioneering French pathologist and neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot [1825-1893], who first intuited that hysteria might be neurologically triggered. He also insisted that men could be just as affected by this blanket disorder and recommended hypnosis as a treatment of choice. Then, Pierre Janet [1859-1947], one of Charcot’s most famous students, was the first to hypothesise a connection between past traumatic events in a hysteric patient’s life and their current symptoms, such as e.g., “dissociation”, a term he first coined. Finally, another student of Charcot and initial admirer of Janet, Sigmund Freud [1856-1939], initially linked hysteria to an earlier experience of sexual abuse in his “seduction theory”.

However, pressured by peers, his entourage or his own fears, Freud later steered away from this connection. Through the development of psychoanalysis and its more contentious concepts such as “penis envy” or “castration complex”, the (mainly female) hysteric patient was usually perceived as harbouring repressed sexual desires or fantasies.

Hence, hysteria, as a blanket condition for a number of neuroses affecting primarily women, but also increasingly soldiers (hence men), remained a diagnostic staple of psychiatric care in the first half of the 20th century.

Largely overlapping with the Vietnam war, it was the so-called second wave of feminism, between the 1960s and 1980s, that revived the controversy about the link between “hysteria” and “abuse”. The questioning of patriarchy’s oppressive role in all domains pertaining to a woman’s everyday life brought up, among many other issues, fundamental questions about the treatment of women’s minds and bodies.

The feminist movement exposed the concept of “hysteria” as a consequence of patriarchal oppression and some feminist authors even reclaimed it as a sane reaction to insane conditions. As aptly put by author Mark Micale, until then hysteria had “served as a dramatic medical metaphor for everything that men found mysterious or unmanageable in the opposite sex” (Micale; 1989).

Building on the seminal work on neurosis by one of Freud’s first female critics, feminine psychiatry pioneer Karen Horney [1885-1952], many of the tenets of classical psychoanalysis were heftily disputed. Feminist activists and theorists such as e.g., Luce Irigaray [1930] or Shulamith Firestone [1945-2012], were not just incensed at the masculinist bias of psychoanalysis. Due to its focus on the personal rather than the political, they also condemned what they perceived as a myopic perspective that failed to foreground the systemic, society-wide oppression of women.

Hence, second wave feminism began to expose the multiple layers of specific trauma women were subjected to. In the 1970s and 80s, the “gendering” of trauma led to an explosion of publications on topics ranging from domestic violence, (marital) rape, incest and reproductive issues to education, workplace as well as broader political and societal challenges.

As women’s physical and mental health became increasingly spotlighted and diagnostic categories underwent further refinement, the diagnosis of hysteria gradually fell into disuse. It was removed from the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, just as PTSD was included in 1980.

One of the last categories to be recognised in the world of trauma was children.

Forensic scientist Auguste Ambroise Tardieu [1818-1879] can be considered a lonely pioneer in this domain. Indeed, he was the first to broach and combat the hitherto taboo issue of physical and sexual abuse of children in the mid-19th century.

But it took another century for modern state-driven child welfare to truly take off.

A seminal milestone on the way to recognising and treating child abuse was the work of American paediatricians C. Henry Kempe, his wife Ruth Kempe and their colleagues. In 1962, they were the first to name the complex web of symptoms they discovered in their paediatric practice as “battered child syndrome”.

Over the course of the next decades, many studies emerged, detailing the myriad ways in which children could be lastingly wounded – both physically and psychologically – and mostly by their parents or carers. Beyond active and direct bodily harm through physical or sexual abuse, neglect, emotional abuse, inconsistent parenting (due to separation, incarceration,substance abuse or psychiatric disorders), as well as the witnessing of violence in the home were highlighted as “adverse childhood experiences” (or ACEs).

In fact, academic research as well as social work and clinical psychology increasingly converged in their assessment of childhood trauma as a complex, lasting and/or recurrent phenomenon, often persisting into adulthood.

Instead of the vague and non-child-specific umbrella term “trauma- and stress-related disorders”, at least two diagnoses for childhood trauma were suggested by experts in the field. Psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk and colleagues proposed “developmental trauma disorder” (DTD). However, although it was (and still is) perceived by many therapists as a useful unifying category, it was not included in the DSM-5.

“Complex PTSD” (or C-PTSD), the term recommended by psychiatrist Judith Herman [1942] for recurrent and/or persistent (childhood) trauma, did not make it into the DSM-5 either. However, it was included in the 11th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) and is increasingly recognised as a useful diagnostic category in the field of trauma treatment and research.

In addition, Herman's distinction between so-called Type I trauma, which is triggered by a single event, and Type II trauma, which is caused by repeated or chronic stressors, has become increasingly popular.

The “CDC-Kaiser Permanente adverse childhood experiences (ACE)” study in the late 1990s was the next biggest landmark in the field. Featuring 17,337 respondents recruited through the managed care consortium, the study uncovered a particularly humbling picture of violence against children in the United States. While 36.1% of respondents reported no ACEs, 26.0% reported one, 15.9% reported two, 9.5% reported three and 12.5% reported four or more (CDC; 2021).

This study was the first to show the compounding and long-term effects of multiple ACEs on the health and wellness of the individuals interviewed.

Finally, another form of pervasive trauma openly emerged in the latter half of the 20th century. Beginning in the immediate aftermath of World War II with the liberation of Nazi concentration camps in Europe, it featured the methodical persecution of Jewish, Sinti, Roma and other individuals for their culture, their beliefs, their political orientation and their supposedly racial or ethnic phenotypes.

Shortly thereafter, the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s highlighted the systemic oppression of the African American population in the United States. In parallel, American and Canadian First Nations reconnected with their initial resistance to the dominant culture and began to re-examine their traumatic history.

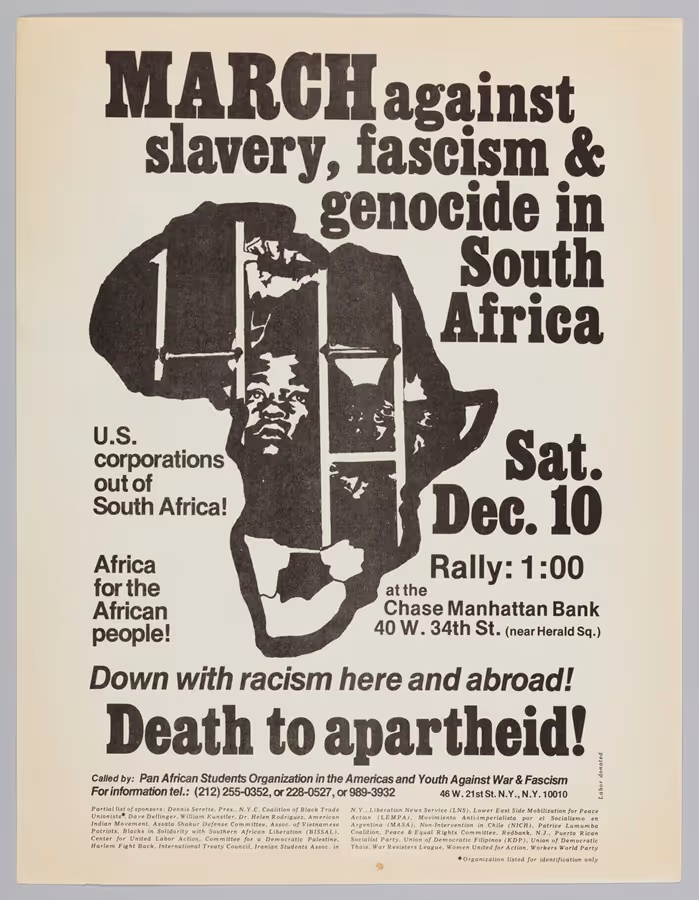

More globally, trauma awareness was also stoked by political developments such as Apartheid in South Africa or the Cambodian and Rwandan genocides. In the academic world, postcolonial theorists began to revisit and revise the hegemonic historical narratives of the metropoles – highlighting the traumatic load of formerly colonised countries.

Likewise, the ongoing struggles of civilian movements centred on e.g., disability, sexual orientation, displacement, chronic health conditions or ecological emergencies unearthed other forms of potential trauma.

Last but not least, research on the economic dimension of trauma demonstrated that chronic deprivation, lack of opportunities, work discrimination etc. could also catalyse traumatic stress.

So, if anything, our small but intense journey through the taxonomy of trauma will have demonstrated that trauma is ubiquitous. Men (not just soldiers!), women, children as well as all manner of “minority” individuals and groups can be exposed to trauma and develop long-term consequences such as PTSD, as well as other forms of mental and physical illness. Moreover, trauma may be compounded by transgenerational and intersectional aspects.

What do we mean by that?

Intense trauma may not only affect an individual or a group at a given time. It may develop a historical dimension when individuals or groups are severely affected by it over the long term.

In this case, it cannot be contained within one generation but instead reverberates physically and psychologically over two to three generations, or more. Indeed, instances of intergenerational trauma have been linked to survivors of lengthy civil wars or genocides and their immediate descendants. But intergenerational trauma is also characteristic of the experience of indigenous groups or enslaved peoples who have encountered injustice for centuries, such as e.g., the Australian First Nations.

“Intersectional”, in turn, refers to the positional dimension of trauma between different systems of power and oppression. For example, a female child of colour with a disability may accumulate complex, race-, gender- and disability-based trauma and still encounter an external trauma such as a car accident or an earthquake. So, depending on their identities and circumstances, individuals may experience superposed levels of trauma.

However, given adequate and sufficient resources, many individuals manage to overcome trauma and may even develop a form of resilience.

But before we go into resilience and trauma prevention, our next instalment will first explore the physical and psychological impacts of the trauma categories we have just evoked as well as paths towards recovery. So, stay tuned!

++++

“Rambo: First Blood | Emotional Scene | Rambo's Breakdown”. StudioCanalUK. YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PtWHgkNH5yU

“First Blood”. Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Blood

Huston, John. “Let there be light”. American documentary, 1946. Restored version available online: https://www.filmpreservation.org/preserved-films/screening-room/let-there-be-light-1946

Crocq, Marc-Antoine, and Louis Crocq. 2000. “From Shell Shock and War Neurosis to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A History of Psychotraumatology.” Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2 (1): 47–55. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/macrocq. Online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/macrocq#d1e124

Rousseau, Danielle. “A Brief History of Trauma and PTSD”. Boston University. August 11th,2024. Online: https://sites.bu.edu/daniellerousseau/2024/08/11/a-brief-history-of-trauma-and-ptsd/

Friedman, Matthew J. “PTSD History and Overview”. s.d. PTSD: National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veteran Affairs. Online: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/history_ptsd.asp

„History of PTSD”. (May 15, 2025). Trauma dissociation.com. Retrieved May 15, 2025 from https://traumadissociation.com/ptsd/history-of-post-traumatic-stress-disorder.html.Read more: https://traumadissociation.com/ptsd/history-of-post-traumatic-stress-disorder.html

McVean, Ada. “The History of Hysteria”. Office for Science and Society. Montreal: McGill University. 31 Jul 2017. Online: https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/history-quackery/history-hysteria

Micale, Mark S. Hysteria and its Historiography: A Review of Past and Present Writings (II). History of Science, 1989, 27(4), 319-351. doi:10.1177/007327538902700401 (Original work published 1989). Online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/007327538902700401

Tasca C, Rapetti M, Carta MG, Fadda B. Women and hysteria in the history of mental health. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:110-9. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110. Online: https://clinical-practice-and-epidemiology-in-mental-health.com/VOLUME/8/PAGE/110/

“Hysteria”. Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hysteria

“Female hysteria”. Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Female_hysteria

“Jean-Martin Charcot”. Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Martin_Charcot

“Pierre Janet”. Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pierre_Janet

„Psychoanalytic Feminism“. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. First published May 16,2011; substantive revision Dec 5, 2023. Online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/feminism-psychoanalysis/

Yadav, Riya. “Sigmund Freud and penis envy – a failure of courage?”. The British Psychological Society. 08.05.2018. Online: https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/sigmund-freud-and-penis-envy-failure-courage

“Feminism and Psychoanalysis”. Encyclopedia.com, s.d. Online: https://www.encyclopedia.com/psychology/dictionaries-thesauruses-pictures-and-press-releases/feminism-and-psychoanalysis

Kempe CH, Silverman FN, Steele BF, Droegemueller W, Silver HK. The Battered-Child Syndrome. JAMA. 1962;181(1):17–24.doi:10.1001/jama.1962.03050270019004. Online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/327895

Van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. New York: Viking Press, 2014.

Herman, Judith Lewis. “Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma”. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Volume 5, Issue 3, July 1992, 377-391. doi:10.1002/jts.2490050305. Online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jts.2490050305

“About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study”. Center for Disease Control (CDC), Violence prevention. Last reviewed: April 6, 2021. Online: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/aces/about.html

„Adverse childhood experiences”. Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adverse_childhood_experiences#Adverse_Childhood_Experiences_Study

“Racial Trauma”. Mental Health America. Online: https://mhanational.org/resources/racial-trauma/

Subica AM,Link BG. “Cultural trauma as a fundamental cause of health disparities”. SocSci Med. 2022 Jan;292:114574. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114574. Online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9006767/

Bailey Lanier, Lucija Ozic-Paic, Sherazade Prasetyo, Ariel Reuveni Cohen and Ariel Wang. "The psychological impacts of Genocide". OxJournal Psychology. Apr 3 2024. Online: https://www.oxjournal.org/the-psychological-impacts-of-genocides/

Wait, Liana. “Mitigating the Multigenerational Impacts of Trauma”. Dartmouth College, Faculty of Arts and Sciences. 1/7/2025. Online: https://fas.dartmouth.edu/news/2025/01/mitigating-multigenerational-impacts-trauma

Illustrations

Aamir Mohd Khan & Sammy Sander / pixabay + epiAge

Lance Reis/ pexels

A. Londe « Attaque de sommeil hystérique » / Wellcome Collection, rawpixel

Kantsmith / pixabay

Cover of Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch / Wikipedia, Public Domain

Flyer announcing a protest against apartheid in South Africa / rawpixel, Public Domain

Back to all posts

Back to all posts