Sugar is sweet and so are you…?

What is your drug of choice?

Mine is definitely sugar. In fact, I think I can even speak for the epiAge team…

You may not find the little white crystals to sweeten your coffee at our headquarters, but when it comes under the guise of chocolate, dried fruit or treats from the local French pâtisserie, we all get weak-kneed. And since sugar is also the essence of carbs, we needn’t even boast a sweet tooth to be “addicted” to pizza, potato crisps or rice noodles…

And it’s not like we don’t know any better – we do. But that’s where the “drug of choice” irony comes in. Like with any addiction, we may choose (or be attracted to) a particular source of pleasure, but physiology seems stacked against us when it comes to controlling the cravings.

Especially since sugar – similarly to alcohol – is not just a societally condoned “poison”, but the very stuff of reward, celebration and sensuous indulgence. And, last but certainly not least, because sugar is mammals’ primary metabolic fuel, making it very challenging to avoid, or at least contain.

The white elephants in the kitchen

But how did we get there? Have sugar and starches always been a problem in mankind’s evolution?

Well, for the larger part of human history, sugar (i.e. primarily mono- and disaccharide sunder the guise of glucose, fructose or galactose, respectively sucrose and lactose) was not an issue because, with the rare exception of honey, it was never available in such vast amounts or concentrated forms as we enjoy it today. Under the guise of vegetables, grains, dairy products or occasional fruit, it came in smaller quantities and always neatly “packaged” in fibre, protein or fat, making it smoother to metabolise.

From this perspective, sugar’s meteoric rise from niche remedy and coveted spice in the European Middle Ages to cheap energy fix for exhausted factory workers in the 19th century is truly stunning.

Originally derived from exotic sugarcane cultivated in Southeast Asia, it rapidly became a luxury staple in the 18th century – simultaneously powered by the blood-thirsty slave-trade and the industrialisation of production. But it was German physicists Andreas Sigismund Marggraf and Franz Karl Achard’s exploitation of the more local potential of sugar beets that truly propelled it to the status of cheap global commodity over the course of the 19thcentury.

Ever since, sugar has infiltrated just about every processed food you can think of because its talents extend well beyond sweetening to include e.g. food preservation, bulking or texturing.

Refined starches (i.e. polysaccharides) underwent a very similar trajectory. Once the province of the wealthy, white flour gradually conquered the masses, thanks to improvements in milling and sifting technologies. Through these processes, grains – whether wheat, rye,maize/corn, or rice – could boast an increased shelf life. But they also lost their fibre and micronutrient “packaging”, turning them into glucose time bombs for the human metabolism.

High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is the latest (b. 1964) and sweetest child in this cloying progeny. Interestingly, it is obtained through the complex industrial processing of corn starch. In this case, the starch’s polysaccharides are broken down using high-temperature enzymes and the end-product is a solution with varying amounts of fructose versus glucose. One of its chief uses is in the production of soft drinks or sodas. Here again, the sugar is “naked”, hence ready to trigger havoc in the human organism.

Now, do all these refining processes remind you of anything? We will say no more… for now, at least.

A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down – in a most delightful way!

So, what about today?

In many contemporary societies, exhausted factory workers have been replaced by overwrought service economy workers. But the sugar dilemma has hardly changed.

Indeed, we challenge you to find a workplace or, for that matter, a home that is totally immune to the charms of the white stimulant over the course of a regular work or school day. From croissants and breakfast cereals to sandwiches, chocolate bars and pretzels, most of our meals and snacks are laced with the pick-me-up power of refined sugar and starches.

Indeed, the consumption of sugar has literally sky-rocketed over the last couple of centuries. Just one example from Germany should suffice to illustrate this global trend: from about 6 kg per capita in the mid-19th century, consumption has risen to 21,8 kg in the postwar period (1950/51), climbed to a staggering 37,6 kg in 2013/2014, before dropping to a still very worrying 33,2 kg in 2022/2023. However, compared to the “highs” reached by Barbados (52,86) or even Belgium (48,27) in 2020, Germans’ glucose intake appears almost modest – even if not at all role-model worthy.

But finding reliable statistics on countries’ sugar consumption proves a challenge in and of itself. Obviously, sugar consumption is subject to variations across place and time but beyond that, international comparisons are often hindered by the use of different measurement units. Indeed, even within the same study or article, sugar consumption may be given in kilos, pounds, spoonfuls or even cubes. Hence, blending mass, count and volume units makes for a particularly confusing overall picture.

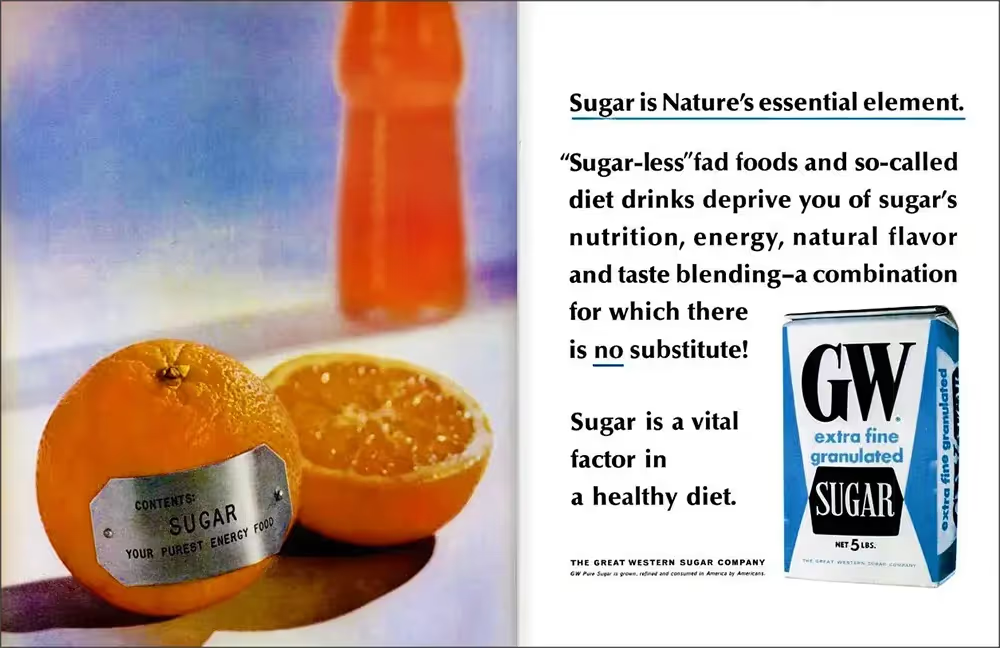

Beyond the usual metric versus imperial traditions, this state of affairs is reminiscent of one of the numerous smokescreen tactics enrolled by the sugar industry and its lobbies (or should we say “cartel”?) to mislead the public about sugar consumption and its benefits, and this from the very beginning of its mass commodification.

Over the years, there have been a number of contributions striving to break the sugar omertà. A true milestone publication was late British Professor of Nutrition John Yudkin’s book “Pure, White and Deadly” in 1972, in which he elaborated on the manifold metabolic disturbances caused by sucrose. In retrospect, the crushing backlash Yudkin had to contend with appears incredible, since he was heavily criticised not just by the sugar industry but also by his peers. Yudkin’s public rehabilitation took years and bolstering by the work of e.g. science journalist Gary Taubes and paediatric endocrinologist Robert Lustig, among many others.

But one of the biggest sugar bombs to explode in recent years was the publication of an article in 2016 in the Journal of the American Medical Association by three University of California San Francisco scientists, Cristin E. Kearns (Associate Professor in Preventive and Restorative Dentistry), Laura A. Schmidt (Professor of Health Policy) and Stanton A. Glantz (Professor of Tobacco Control). It provided an analysis of internal documents detailing the Sugar Research Foundation’s efforts in the 1960s and 1970s to lay the blame for coronary heart disease on fat and cholesterol instead of sucrose, despite early warning signs of a link between CHD and sugar in the 1950s.

These developments along with a growing body of research on the nefarious effects of sugar on the human metabolism (more about that in our next instalment), not to mention the increasing popularity of Atkins and Paleo style diets mean that sugar is being belatedly but surely recognised as a global public health nemesis.

So, why do we continue to eat it?

Give us this day our daily dose and lead us not into temptation…

Is it because sugar is really a drug? Well, despite significant research in neurobiology as well as progress in neuroimaging, the jury is still out on this issue…

Indeed, the ambivalence of sugar dependence seems to be linked to its position at the intersection between “substance-related addictive disorders” and “non-substance-related disorders”. The former category covers drugs such as alcohol, caffeine, opioids, barbiturates or nicotine whereas the latter focuses on habit- or activity-related addictions labelled as “behavioural”. These include activities that are not per se addictive (for most people at least) but which can become so – from gambling to dieting, exercising, having or watching sex, gaming, shoplifting and… eating.

It may be for this reason that sugar dependence is not yet included in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)even though it shares many of diagnostic categories and criteria of substance and non-substance abuse disorders. As noted by Wyss, Avena and Rada (2018), in animal studies, sugar triggers most of the criteria in the “Impaired Control” category: from “using larger amount for longer than intended”, to “craving”, and “repeatedly attempting to quit and/or control abuse”. The “Social Impairment” category may be less prominent with sugar than in other addictions but both “Continued Use despite Risk” and “Pharmacological Criteria” – with issues such as “tolerance” and “withdrawal” – seem relevant to sugar abuse.

On a neurobiological level, sugar like most other addictive substances and behaviours triggers the reward centre of the brain by catalysing a flow of the neurotransmitter dopamine. As witnessed by Bijoch, Klos et al. (2023) using whole brain c-Fos imaging – sugar, like cocaine, appears to trigger a widespread activation of distant neuronal networks (especially upon first exposition, for sugar) as well as the formation of silent synapses, thus demonstrating synaptic plasticity after “reward treatments”.

In fact, rats exposed to both substances initially tend to gravitate towards sugar more often than cocaine because it provides more rapid gratification. But if delays are experimentally built in for sugar, they will gradually shift their preference towards cocaine. However, different behaviours can arise, depending on the animals’ level of hunger/deprivation or satiety, the intensity and frequency of exposure, etc. Also, there are a number of hurdles in the design of comparative studies beginning with e.g. the administration of sugar versus cocaine (the latter’s bitter taste means that it is usually injected instead of offered in liquid form). How these findings apply to human subjects remains to be seen since ethical and practical considerations inevitably preclude the types of experiments conducted in animal model studies.

Nevertheless, even if sugar as we know it today may never quite fit the addiction bill, as it straddles the realms of substance and behaviour reward, it appears amply clear that we are not doing ourselves any favours by bingeing on macaroni cheese and chocolate cake.

But beyond what sugar does to our brains, our next article will examine the body-wide damage sugar wreaks, affecting both our health and our longevity, before exploring potential strategies to regain control of our sweet urges…

So, stayed tuned!

Sources (last accessed 24.04.2024)

Wikipedia, “Sugar”. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sugar

Wikipedia,“Zucker”. Online: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zucker

Wikipedia, “History of Sugar”. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_sugar

Added sugar: Where is it hiding? Harvard Health Publishing, November9, 2019. Online: https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/added-sugar-where-is-it-hiding

Wikipedia, “High Fructose Corn Syrup”. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High-fructose_corn_syrup

Wight, Heather, “The history and processes of milling”, originally published by HumJournal, January 25, 2011, Online: https://www.resilience.org/stories/2011-01-25/history-and-processes-milling/

Bosma, Ulbe/Made by history, “How the world got hooked on sugar”, Time, October 31, 2023. Online: https://time.com/6329462/history-sugar/

Brodman, Romeo, Zucker. „Die Geschichte im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert“. Das Pauli Magazin, 15.01.2022. Online: https://daspaulimagazin.ch/de/freitext/die-geschichte-des-zuckers-im-20-und-21-jahrhundert

„Pro-Kopf-Konsum von Zucker in Deutschland inden Jahren 1950/51 bis 2022/23 (in Kilogramm Weißzuckerwert)“, Statista,2024. Online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/175483/umfrage/pro-kopf-verbrauch-von-zucker-in-deutschland/

„Pro-Kopf-Verbrauch von Zucker weiter gesunken“, Bundesanstalt für Lanwirtschaft und Ernährung, s.d. Online: https://www.ble.de/SharedDocs/Meldungen/DE/2021/210517_Zuckerbilanz.html

“Sugar Consumption Per Capita“, HelgiLibrary, 2021. Online: https://www.helgilibrary.com/indicators/sugar-consumption-per-capita/

“Sugar Consumption Per Capita in USA”, HelgiLibrary, 2021. Online: https://www.helgilibrary.com/indicators/sugar-consumption-per-capita/usa/

“Sugar: The Most Evil Molecule”, Podcast with Sam Kean (Senior Producer: Mariel Carr), Science History Institute, October 12, 2022. Online: https://www.sciencehistory.org/stories/disappearing-pod/sugar-the-most-evil-molecule/

Langer, Sarah, „Die ungesüßte Wahrheit über Zucker“, National Geographic, 31.01.2024. Online: https://www.nationalgeographic.de/wissenschaft/2024/01/die-ungesuesste-wahrheit-ueber-zucker

„Die Märchen der Zuckerlobby“, foodwatch,13.03.2020. Online: https://www.foodwatch.org/de/die-maerchen-der-zuckerlobby

"Rare Historical Photos: Misleading vintage ads about the dietary benefits of sugar", 1950s-1960s, Rare Historical Photos, s.d. Online: https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/sugar-vintage-ads/.

Yudkin, John, Sweet and Dangerous. New York: Peter H. Wyden 1972. / Yudkin, John, Pure, White and Deadly: The Problem of Sugar. London: Davis-Poynter, 1972.

“Pure, White and Deadly”, Wikipedia. Online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pure,_White_and_Deadly

Taubes, Gary, "What if It's All Been a Big Fat Lie?". The New York Times, 7 July 2002. Online: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/07/07/magazine/what-if-it-s-all-been-a-big-fat-lie.html

Lustig, Robert, "Sugar: The Bitter Truth", University of California Television, 26 May 2009. Online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBnniua6-oM

Kearns CE, SchmidtLA, Glantz SA. Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents. JAMA Intern Med.2016;176(11):1680–1685. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394. Online: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/2548255

Schaefer, Anna, Yasin, Kareem, “Experts Agree: Sugar might be as Addictive as Cocaine”, Healthline, May 30, 2023. Online: https://www.healthline.com/health/food-nutrition/experts-is-sugar-addictive-drug#What-is-added-sugar?

Krans, Brian, Sugar is a “Drug” and Here’s How We’re Hooked, Healthline, September 18, 2023. Online: https://www.healthline.com/health-news/addiction-sugar-acts-like-drug-in-the-brain-and-could-lead-to-addiction-091813

„Addiction“, Cleveland Clinic, s.d. Online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/6407-addiction

Wiss DA, Avena N and Rada P (2018) Sugar Addiction: From Evolution to Revolution. Front. Psychiatry 9:545. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00545. Online: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00545/full

Olszewski, P.K., Wood, E.L., Klockars, A. et al. Excessive Consumption of Sugar: an Insatiable Drive for Reward. Curr Nutr Rep 8, 120–128 (2019). Online: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-019-0270-5 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13668-019-0270-5

Greenberg, D.; St. Peter, J.V. Sugars and Sweet Taste: Addictive or Rewarding?, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189791. Online: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/18/9791?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fdzen.ru%2Fmedia%2Fid%2F5e4d30b75033cf582d875f61%2F654b322dfe9a20342120083f

Samaha, AN. Sugar now or cocaine later?. Neuropsychopharmacol. 46, 271–272 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-020-00836-z. Online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41386-020-00836-z#citeas

Bijoch, Ł., Klos, J., Pawłowska, M. et al. Whole-brain tracking of cocaine and sugar rewards processing. Transl Psychiatry 13, 20 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02318-4. Online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-023-02318-4#citeas

Illustrations

Alexander Grey / pexels

Rodolfo Clix / pexels

Pexels / Pixabay

Köhler, Franz Eugen, „Papaver Somniferum“, Köhler‘s Medizinal-Pflanzen, 1897. List of Koehler Images, Public Domain. Online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=255422

Rare Historical Photos: Misleading vintage ads about the dietary benefits of sugar, 1950s-1960s. Online: https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/sugar-vintage-ads/.

Bulat / pexels

Henri Mathieu / pexels

Back to all posts

Back to all posts